In the Spring of 2021, a private client south of Glasgow approached us to plant a wee forest to provide screening and noise reduction from a main road, in the case that the adjacent Spruce plantation was ever felled. The forest would therefore need to be dense and quick growing. However, the land available for planting was fairly small, at around 100 metres long and an average of 5 metres wide.

Researching the best solution led to my discovery of the Miyawaki forest regeneration method. This was initially developed in Japan in the 1970s, with the aim of restoring resilience to forests. Its comparatively fast plant density seemed to be applicable to my client’s needs.

See my previous post, ‘Why use the Miyawaki method?’

Forest regeneration method

For this method, it is recommended that around 40 individual species are planted. These need to include plants that would occupy all of the forest layers (herbaceous, shrub, understory, canopy). The species should be chosen according to potential natural vegetation (PNV).

The species are densely planted, mimicking natural regeneration. The trees are expected to grow around one metre in height per year.

Plant-suitability, mutual aid and high biodiversity should mean that the forest has increased resilience to climate, climate-change and to pests & diseases.

Research and design

A fair bit of research and investigation was required prior to designing and planting the forest. I undertook several on-site investigations as well as a quantity of desktop research.

Soil type, bulk-density, drainage, and pH

The UK Soil Observatory (UKSO) website indicated the site had a clay-loam to sandy-loam soil with a glacial till subsoil. Trial pits revealed a deep, clay-dominated soil. Earthworms were present, indicating that the soil would be suitable for planting without remediation.

I collected soil from three different locations in order to measure bulk density. This ranged from 0.7-1.35 g/cm3, largely agreeing with the UKSO figure of 0.94 g/cm3. Clay soil is reported to be suitable for planting at bulk densities of less than 1.47 g/cm3. Clay soil is good at holding water and nutrients.

The soil was mildly acidic (between 6.0 and 6.5 pH) which is suitable for most trees.

The percolation test (to determine drainage rates) indicated drainage rates of 400 millimetres per hour at the centre point of the woodland. A rate of more than 250 millimetres per hour is considered to be well-drained, so the soil should be suitable for most species.

There was a gentle slope, rising from south to north. It was known that the southern wend of the woodland was prone to some water-logging events. Therefore it was planned to plant more water-tolerant species in this area. There were some existing land drains in the vicinity, though they were in need of maintenance. When they are fully functional, they will help to reduce water-logging events in the southern forest.

I concluded from these investigations that no soil remediation would be necessary.

Local climate and climate-change

Local climate is an important factor when choosing the right trees for the site. The Met Office website provided information regarding 30 years averages for the planting area:

- Temperature range: 6-19 Celsius (above average for Scotland).

- Sunshine: 50 hours per month (well below average for Scotland).

- Rainfall: 118 millimetres per month (slightly below average for Scotland).

The Met Office and UK Government websites also provided information on predicted climate change, highlighting how forest-resilience will become even more important for ensuring that the plants and trees thrive:

- Over the next 30 years (at the site location) it can be expected that winters will become wetter and summers will be drier, with increased drought events, more intense periods of rain and more wind.

- The growing season will be longer.

- The numbers of pests and diseases is expected to increase.

By choosing species according to potential natural vegetation, and by planting with initial high levels of biodiversity, we can give the forest the best chance of long-term survival.

Aspect and shelter

The trees would be protected to the northeast by an early-mature Spruce plantation (growing on neighbouring land) and to the west by an existing area of mature mixed-species woodland. The wee forest would enjoy light from the southeast to southwest, with the northern part of the forest becoming shaded towards the middle of the afternoon.

Due to the semi-urban location, there were a lack of native woodlands in the area that could be used to determine the local native-species. However, the information that I had gathered would give me a list of suitable plant species.

Species selection and sourcing

I then consulted a number of resources – though mainly Forest Research’s Ecological Site Classification website – to find out what species would be best suited to the location.

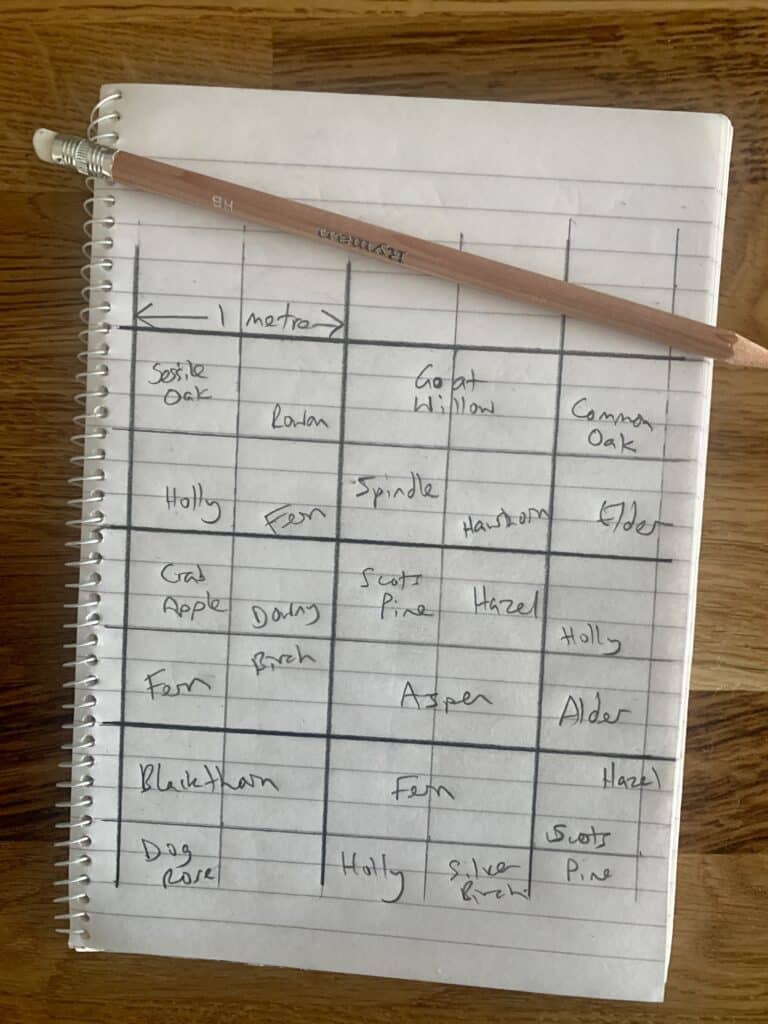

I drew up a list of 28 suitable trees and shrubs with 13 herbaceous, 4 shrub, 3 understorey and 7 canopy species. In addition to this, I ordered a woodland wildflower seed mix containing 17 species. Finally, I ordered around 9 types of fern.

We planned for over 50 different species, however only 18 of the 28 tree and shrub species were available from our preferred tree supplier, making a total of around 44 species.

The planting area was approximately 500 square metres. In total, we ordered 1400 tree and plant species, around 100 ferns and 1 kilogram of seeds.

It was important to source trees and plants with a provenance as close to the site conditions as possible. I also chose suppliers based on their species range, product quality, production standards and adherence to regulations.

Cheviot Trees, based in Berwick upon Tweed, supplied the cell-grown trees and shrubs. Cell-grown trees have an intact root-system, high survival rate, are quick and easy to plant and are inexpensive to purchase. Cheviot Trees use seed collected in the UK and can match the provenance to the planting site. They have excellent accreditations and plant health procedures.

The ferns were sourced from Binny Plants in West Lothian. All of their ferns are grown on site, and are of excellent quality.

I commissioned Scotia Seeds to create a shade-tolerant native-woodland wildflower seed mix. This company are based in northeast Scotland and all of their seed is from wild seed sources growing in Angus. They are signatories to the ‘Flora Locale Code of Practice for Collectors, Growers and Suppliers of Native Flora’. Their seeds are quality tested for germination and purity, as validated by the International Seed Testing Association.

Wee Forest planting method

My method for creating the wee forest is as follows:

- Mark out the planting area.

- Remove or transplant existing shrubs.

- Kill the grass using glyphosate (the preferred option was to remove the turf layer but for various reasons this was not viable).

- Wait four weeks for the grass to die and start to decompose.

- Apply a layer of mulch to protect the soil. Mulch was available on site. This was composed of various types of organic matter, such as grass cuttings, leaves and small woody material.

- Plant through the mulch at around 3 plants per square metre. The species were mixed together, with more water-tolerant species to the south of the woodland, and more shrubs and ferns on the woodland edge.

- Apply the seeds by hand.

This forest regeneration method is fairly straightforward, however it needs to be amended to suit the site. Sometimes soil remediation will be required, mulch may need to be brought in and protection from herbivores and humans will be required.

However its simplicity means that it can be adapted to planting forests of all sizes and in almost any situation. It has been used to reforest degraded land, tropical clear-fell sites, roadside verges, and even roundabouts.

Timescale and considerations

No soil remediation was considered to be necessary.

No machinery was used within the planting area, so as to prevent soil compaction. No tree-guards nor deer-fencing were used, as the site is relatively free of deer and rabbits. In any case, it is unlikely that herbivores would inflict significant damage to so many plants.

I undertook the research into the Miyawaki method over a period of months. Once I had gathered the information I required, it was a fairly straightforward process to carry out the preparation work. Site investigations, research, design and plant-sourcing took around two workforce-days.

Site preparations and planting took place in November 2021. In total, this took eight workforce-days. This may seem like a lot, but as the forest will not require management after a couple of years, this time will be saved in the future.

As of May 2022, the forest has only just started waking up, though there is plentiful life to be seen. I will add more photos as the forest develops.

If you would like help with planning a wee forest of your own, please do get in touch. Our ‘Enquiry’ form is short and simple, whereas our ‘Send More Details’ form will allow you to provide location details and documents such as plans and drawings.

About the author

Mike Charkow has been working with trees since 2009, though he has been climbing them since he could walk. He started out as a tree surgeon then moved into arboricultural consultancy. Mike is continually learning about trees, soil, bats and all related matters to keep expanding his knowledge base.